Why limiting choices creates better flow in UX design and how applying the Tech Lead Pattern turns AI from a chaotic coding assistant into a reliable strategic partner. Better UX comes from limiting choices, not expanding them. Better AI-assisted prototyping comes from structured planning, not reactive prompting. A Unity prototype comparing God of War and Hogwarts Legacy stair navigation revealed both principles in action and demonstrated how cognitive load theory applies equally to players and developers.

The Paradox of Player Control

This year, I finished two excellent games: God of War and Hogwarts Legacy. Both are masterfully crafted, both are critically acclaimed, yet their UX choices diverge in small moments that matter. One tiny scene told me a big story: navigating obstacles.

In Hogwarts Legacy, you maintain full control while navigating steps. That freedom sounds great in theory, player agency is sacred, right? But in practice, it often leads to awkward collisions with railings, brief moments of disorientation as you adjust your angle, and that annoying shuffle when you catch a stair edge wrong. You’re fighting the controls instead of enjoying Hogwarts.

In God of War, something different happens. The game quietly reduces unnecessary degrees of freedom as Kratos approaches obstacles. The transition is so subtle you might not even notice it consciously. Your input still matters, but the system gently guides your spatial alignment. You stay centered on the path, your rotation aligns smoothly, and you just… flow. It’s a clean application of Cognitive Load Theory: remove the mechanical effort of alignment, and the player’s attention returns to the world and the narrative.

This wasn’t about one game being “better” than the other, both are phenomenal. It was about a specific UX choice that revealed something profound: smart constraint is a feature, not a limitation.

The Problem With “Freedom”

Let’s dig into what’s actually happening in Hogwarts Legacy’s stairs.

You approach a narrow staircase in the library. You are in full control, with the analog stick responding to every tiny movement. You can walk in any direction, rotate freely, and adjust your angle with precision. It feels like pure player agency, right?

Except here’s what actually happens in your brain:

- Approach stairs at a slight angle

- Notice you’re drifting toward the railing

- Adjust trajectory (minor mental task)

- Start climbing, but the angle is still off

- Bump into the wall (frustration point)

- Correct angle again (second mental task)

- Notice that character orientation feels wrong

- Adjust rotation (third mental task)

- Finally climb smoothly… until the next staircase

Each of those micro-decisions requires cognitive processing. Each correction pulls your attention away from the magical castle around you, the conversation with your companion, the quest objective you’re pursuing. You’re managing spatial navigation mechanics instead of experiencing the world.

Now, contrast this with God of War.

Kratos approaches obstacles. You press forward on the stick. The game detects that you’re near a traversal path and smoothly transitions into a constrained state. Your forward input still controls when you move and how fast, but the game handles the spatial alignment. You stay centered on the path. Your rotation aligns with the stair direction. You don’t bump into walls because the lateral input that would cause those bumps is gently dampened.

The critical insight: you don’t notice this happening. It feels natural. It feels like you’re in control, because you are. You’re just not in control of the parts that don’t matter.

That’s the difference between freedom and smart constraint. One gives you all the decisions. The other gives you only the decisions that actually enhance your experience.

Cognitive Load Theory in Action

There’s a formal framework for understanding this: Cognitive Load Theory, developed by educational psychologist John Sweller in the 1980s.

The core principle is simple: our working memory has limited capacity. Every mental task, whether it’s solving a puzzle, reading dialogue, or adjusting our character’s angle on stairs, consumes some of that capacity. When we exceed our cognitive budget, performance degrades. We make mistakes, miss important information, or feel frustrated without knowing exactly why.

In game design, this translates to a critical question: What should players be thinking about?

When climbing stairs in an action-adventure game, the answer probably isn’t “precise spatial alignment and collision avoidance.” It should be “where I’m going next” or “what that character just said” or “how beautiful this environment is.”

Smart constraints work by identifying low-value decision points, mechanical tasks that consume cognition without adding meaningful choice and removing them. The key word is “meaningful.” Not all decisions are equal.

High-value decisions in an action game might include:

- Which enemy to attack first

- When to dodge or block

- Which path to explore

- How to approach a combat encounter

Low-value decisions might include:

- Adjusting the angle to stay centered on the stairs

- Correcting the trajectory after bumping a wall

- Rotating the character to face the exact right direction

- Managing collision with environmental geometry during traversal

Notice the difference: high-value decisions affect outcomes, strategy, and expression. Low-value decisions are just mechanical overhead.

God of War identifies these low-value moments and applies gentle constraints:

- Gentle auto-alignment: Position lerps toward path center

- Clear traversal states: You know when you’re in “climbing mode” vs. “combat mode”

- Subtle rotation assistance: Character faces the direction they’re moving

- Path helpers: Input is projected onto the intended trajectory

The result? A clumsy, frustrating interaction becomes a satisfying flow. You feel competent because you’re not fighting the controls. The game removes the friction, and what remains is pure forward momentum.

Here’s the paradox that makes this so powerful: less control can create more freedom. When you’re not spending mental energy on spatial micro-management, you’re free to engage with what actually matters. The constraint liberates your attention.

This Pattern Is Everywhere

Once you see this pattern in games, you start seeing it everywhere in digital design. Smart constraints aren’t game-specific, they’re a universal UX principle.

Guided forms are a perfect example. Compare two approaches:

Approach A (Full Freedom):

- Empty form with 20 fields

- All fields visible at once

- No guidance on what’s required

- User figures out order and validation on their own

Approach B (Smart Constraints):

- Progressive disclosure (show 3-4 fields at a time)

- Smart defaults where possible

- Inline validation with helpful messages

- Clear progress indicator

- Required fields marked upfront

Approach B removes the cognitive burden of “What do I fill out next?” and “Did I do this right?” The user is still in complete control of their input, they just don’t have to manage the process architecture.

Checkout flows demonstrate the same principle. Amazon’s one-click purchase isn’t about removing user control, you can still change shipping, payment, or address if needed. It’s about making the default path frictionless by pre-filling decisions you’ve already made before. The constraint (using saved preferences) creates freedom (from repetitive data entry).

Apple’s setup assistants for new devices apply the same logic. They could dump you into settings with full control. Instead, they guide you through a carefully designed sequence, constraining your choices to the essential decisions while applying smart defaults for everything else.

Stripe’s payment integration for developers is another beautiful example. They could give developers full control over every aspect of payment processing. Instead, they provide smart defaults, pre-built UI components, and constrained choices that handle security and compliance automatically. The constraint (following Stripe’s patterns) creates freedom (from payment security nightmares).

The universal principle at work:

- Identify low-value decision points that create friction

- Remove or constrain those decisions with smart defaults

- Preserve agency over high-value decisions that matter

- Make the path of least resistance the correct path

When done well, users don’t feel restricted. They feel empowered because their cognitive resources are focused on what they actually care about.

Building the Prototype: Theory Meets Practice

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” — Attributed to Yogi Berra / Jan L. A. van de Snepscheut

I have a simple rule: never trust a design theory until I can feel it in a build.

For this project, I saw an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. I wanted to validate the “smart constraint” UX principle in a real engine, but I also wanted to investigate the rising hype around “vibe coding.” Could I build a polished, production-grade interaction using strictly AI-assisted prototyping?

To test both the design theory and the development methodology, I created a Unity 3D comparison environment with two identical staircases side by side:

Scene A: Free Control (Hogwarts Legacy style)

- Standard third-person controller

- Full directional control at all times

- Physics-based collision with the environment

- The player manages all spatial decisions

Scene B: Assisted Traversal (God of War style)

- Same controller as baseline

- Path-based constraint system activates near stairs

- Input projected onto path direction (forward/back only)

- Gentle position and rotation correction

- Smooth transitions in and out of the constrained state

For the technical foundation, I utilized Invector’s Third-Person Controller. I chose this asset deliberately to simulate a “brownfield” development environment. In the real world, engineers rarely get a blank canvas, we inherit legacy code, integrate with third-party libraries, and navigate systems we didn’t write. I wanted to force the AI to work within these messy, realistic constraints rather than giving it the easy mode of building from scratch.

The Implementation

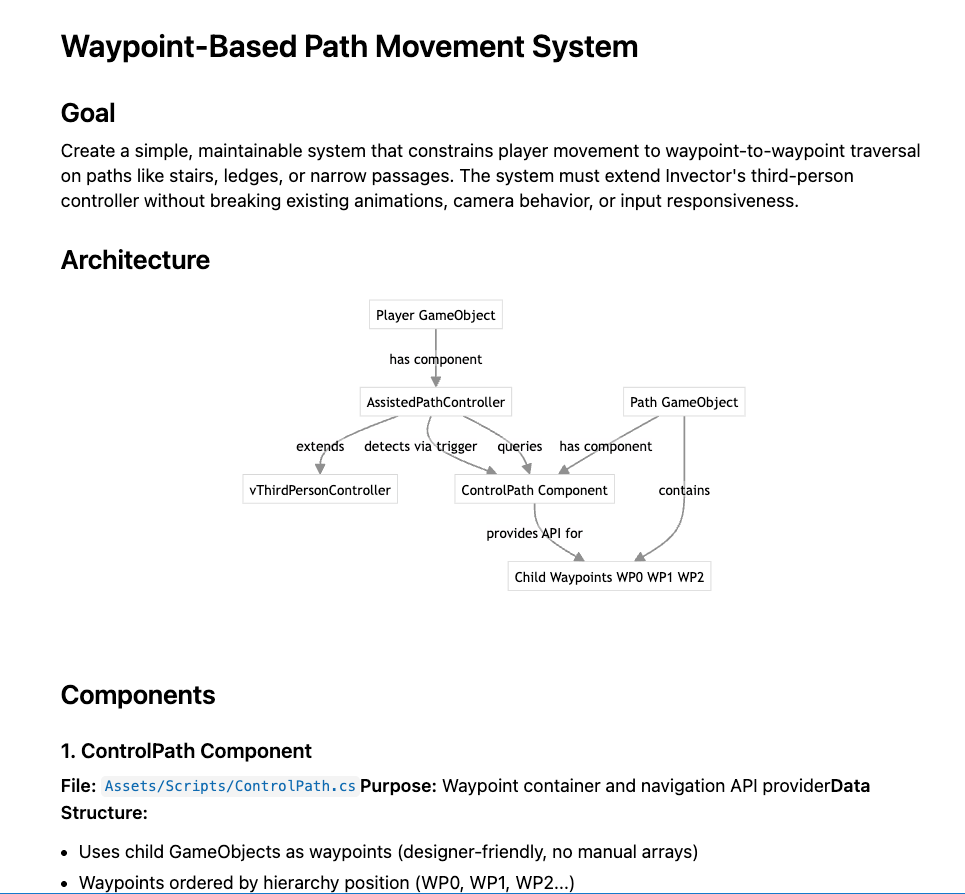

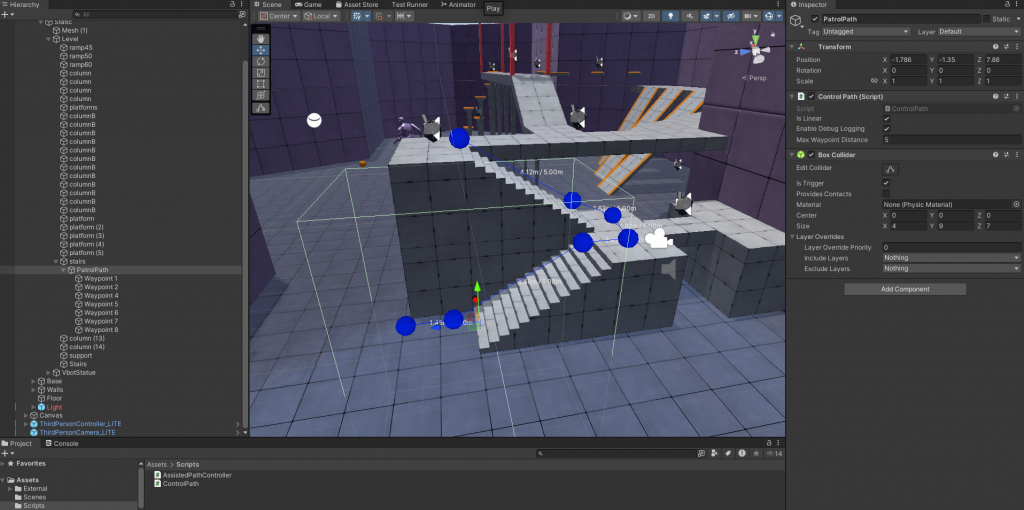

The core system uses a waypoint-based approach. A ControlPath component holds a series of child transforms representing the intended traversal route. When the player enters a trigger volume around the path, the system:

- Identifies the nearest waypoint

- Calculates the direction along the path

- Begins projecting player input onto that direction vector

- Applies gentle position correction to keep the player centered

- Aligns rotation to face the path direction

- Restricts lateral (side-to-side) movement

What the player doesn’t control while on the path:

- Precise spatial positioning (auto-centered)

- Left/right rotation (locked to path direction)

- Lateral movement (dampened or ignored)

This creates the experience of “I’m still in control” while removing the friction of “I have to manage every spatial detail.”

The Visual Feedback System

For designers tuning the system, I added Gizmo visualization in the Unity editor:

- Waypoint spheres showing the path structure

- Lines connecting waypoints

- Color coding: green for acceptable spacing, red when waypoints are too far apart (which would trigger premature path exit)

This makes it easy to author paths that feel good without the need for trial-and-error guessing.

AI-Assisted Prototyping: Two Very Different Approaches

Building this prototype taught me as much about AI-assisted development as it did about UX design. I tried two completely different approaches, and the results were night and day.

The Setup: Unknown Territory

I deliberately chose to extend Invector’s third-person controller for this reason: I had never worked with it before. The architecture was unfamiliar. The code patterns were unknown. This created realistic conditions, most professional development involves working with existing codebases you didn’t write.

I wanted to test “vibe coding” principles with AI-assisted prototyping. Could I, acting as someone with minimal software engineering knowledge, compose complicated tasks by breaking them into small parts and letting Claude (Sonnet 4.5) + Cursor AI figure out the details?

Approach 1: Pure Vibe Coding (Failed)

The Method

My first attempt followed pure vibe coding philosophy to AI-assisted prototyping (minimal structure, maximum speed):

- Minimal planning upfront

- Decompose requests into small, isolated tasks

- Let the AI figure out implementation specifics

- React to problems as they appear

- Trust the AI to maintain architectural coherence

How It Started

I began with a simple vibe coding prompt:

I want to build something cool in Unity.

I'm making a demo to show how God of War has better stair controls than

Hogwarts Legacy.

In Hogwarts you can bump into walls and it feels clunky. In God of War

the stairs are smooth and you don't have to fight the controls.

I want to make two scenes side by side:

- Scene A: normal controls (like Hogwarts)

- Scene B: smooth controls (like God of War)

I have Invector's free third person controller package. Can you help me

set this up?

For Scene B, when the player gets near stairs, make them move smoothly

without bumping walls. They should just go forward/back on the stairs easily.

Let's start!

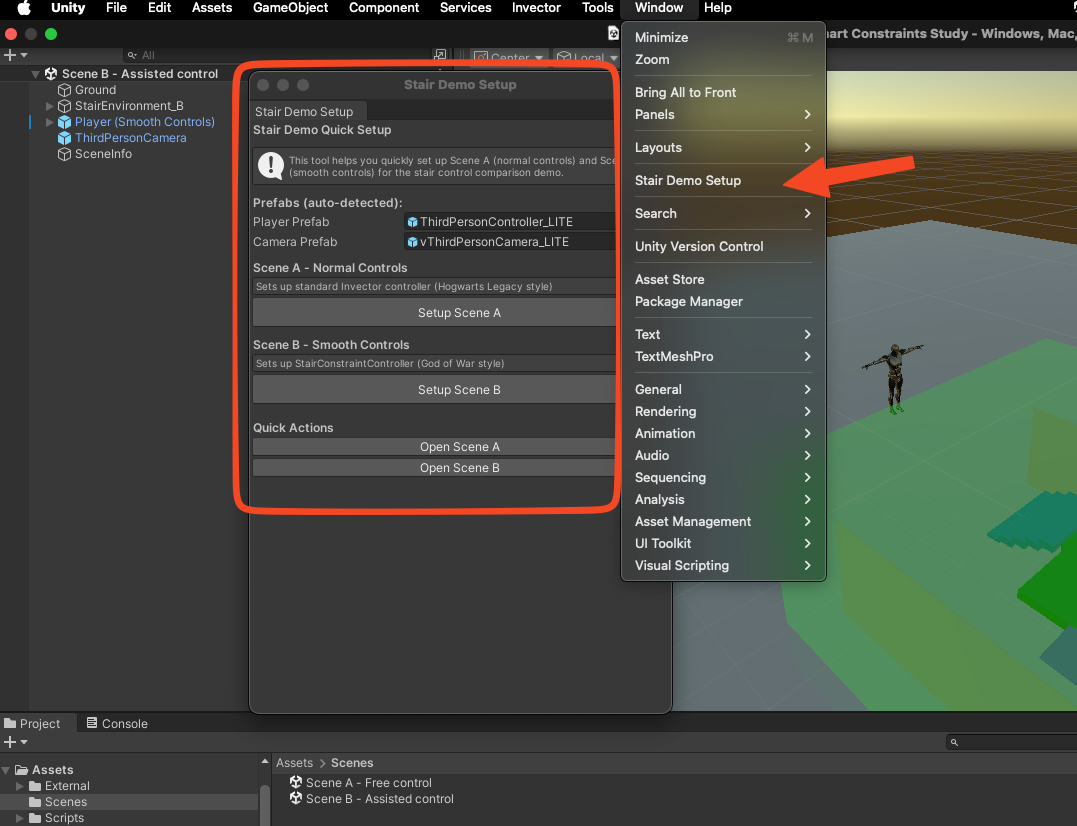

The agent enthusiastically generated an entire project structure:

new file: Assets/Scripts/Editor/ControllerConverter.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/Editor/StairDemoSetupWindow.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/SceneInfoDisplay.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/StairConstraintController.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/StairConstraintUI.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/StairEnvironmentBuilder.cs

new file: Assets/Scripts/StairVolume.cs

new file: CHECKLIST.md

new file: HOW_IT_WORKS.md

new file: INDEX.md

new file: QUICKSTART.md

new file: README.md

new file: SETUP_COMPLETE.md

new file: START_HERE.txt

Impressive output! Seven scripts, six documentation files, even an editor window for setup. The code compiled. It looked professional. It seemed like vibe coding was working perfectly.

Then I opened Unity and the errors flooded the console:

The .meta file Assets/Scripts.meta does not have a valid GUID and its

corresponding Asset file will be ignored. If this file is not malformed,

please add a GUID, or delete the .meta file and it will be recreated correctly

[...15 more similar errors...]

Remember, I’m playing the role of a pure vibe coder here, so I don’t know what these errors mean or what caused them. So I did what vibe coders do: I copied the entire error output and sent it back to the agent with:

I got error messages. Please fix it:

[paste of all 15+ errors]

The Agent fixed them. The errors went away. Success, right?

Except here’s the hidden cost: I just burned through thousands of tokens on errors that could have been prevented. The problem was simple — malformed .meta files from file generation but without understanding the root cause, I couldn’t prevent it from happening again. I was paying (in tokens and time) to fix symptoms, not solve problems.

And this was just the first issue. When I tried to actually test the stair controls…

How It Ended

Disaster. As the complexity increased, the AI completely lost the thread of the system’s logic.

Instead of calculating movement vectors dynamically, the agent started panicking and inserting simple, hardcoded cases to force the behavior I wanted. It began checking specific booleans and writing if/else patches that contradicted the core logic.

As an engineer, I saw this happening. I saw the “spaghetti code” forming. But to stay true to the “hype coder” persona, I ignored it and just prompted: “Fix it.”

The Cycle of Doom

Problem 1: “The player can still rotate left/right on the path. Fix it.”

The Agent added a rotation lock. Worked… until I tested the camera.

Problem 2: “Now the camera movement is broken.”

The Agent added an exception for camera rotation. Worked… until I tested exiting the path.

Problem 3: “The exit transition is janky now.”

The Agent added transition override logic. Worked… until I tested going backward on the path.

Problem 4: “Moving backward doesn’t work correctly.”

The Agent added backward movement handling… which broke the forward movement we already had.

The full source code for this failed attempt is available in the pure-vibe-coding branch of the repository. I’m sharing it not as a working example, but as a cautionary tale. The code is messy, broken, and frankly embarrassing, but that’s precisely why it’s valuable.

I want to highlight a couple of recurring patterns that emerged during this process. These aren’t just random bugs or one-off mistakes. They are systematic evidence of exactly how an AI model’s output degrades without architectural guidance. Understanding these failure patterns is as important as understanding what works.

Sample 1: The “Band-Aid” Timer Instead of fixing the geometry math to detect when a player was actually on the path, the AI panic-coded a timer to forcibly glue the player to the stairs.

// Don't exit immediately after entering - give time to align

float timeSinceEntry = Time.time - timeEnteredPath;

if (timeSinceEntry < minTimeOnPath)

{

if (enableDebugLogging && Time.frameCount % 60 == 0)

Debug.Log($"[AssistedPathController] Too soon to exit (on path for {timeSinceEntry:F2}s, need {minTimeOnPath}s)");

return false;

}Sample 2: Magic Numbers & Arbitrary Logic Here, the AI couldn’t solve the edge case of entering the path at an angle. Its solution? Just double the exit distance based on an arbitrary “influence” float. This is brittle logic that breaks as soon as you change the scale of the game.

// Use a more lenient distance check when path influence is still building

float effectiveExitDistance = pathInfluence < 0.9f ? pathExitDistance * 2f : pathExitDistance;

if (enableDebugLogging && distanceFromPath > pathExitDistance * 0.8f)

{

Debug.Log($"[AssistedPathController] Distance from path: {distanceFromPath:F2}m (exit threshold: {effectiveExitDistance:F2}m, influence: {pathInfluence:F2})");

}This continued for about 15 iterations. Each fix created a new problem. The codebase became a tangled mess of special cases, null checks, and band-aid solutions. I couldn’t roll back to a working state because I didn’t have clear milestones. The code was technically functional, but unmaintainable and fragile.

Why It Failed

Looking back, the failure pattern is clear:

- No architectural oversight: Each fix was tactical, not strategic

- Reactive problem-solving: Whack-a-mole debugging with no systematic approach

- Lost context: AI didn’t understand how each piece affected the whole system

- No review gates: No checkpoints to say “Is this still on track?”

- Accumulating technical debt: Each patch made the next problem harder to solve

The fundamental issue was that I treated AI like a code-generating machine rather than a development partner. I gave it tasks without proper context, and even though Cursor AI automatically added some context, it still returned code without real understanding. As a result, I burned through a fortune in API credits and got nowhere.

Approach 2: Tech Lead Pattern (Success)

After abandoning Approach 1, I started over with a completely different strategy.

The Method

Act as a tech lead would, with clear planning, systematic review, and architectural thinking:

- Understand the system before changing it

- Plan the solution before writing code

- Implement in phases with clear milestones

- Review each phase against success criteria

- Iterate based on analysis, not guesswork

The Process

Phase 1: Architecture Analysis

Before any coding, I asked the agent to analyze the existing project:

Please review and index the project architecture:

- How does input handling work?

- Where are movement calculations performed?

- What's the relationship between controller and camera?

- What are the extension points I should use?

- What constraints do I need to respect?

Provide a technical analysis before proposing any implementation.Claude provided a detailed breakdown of the controller’s structure, identified the appropriate extension points, and flagged potential conflicts (camera control, input processing, physics updates).

Phase 2: Solution Design

Next, I asked for a design proposal:

Based on the architecture analysis, design a path-based traversal system that constrains player movement to waypoint paths while maintaining Invector's animation and input feel.

## Core Requirements

**UX Goal:**

- Remove lateral (left/right) movement on stairs

- Allow only forward/back movement along predefined path

- Maintain player agency over timing and speed

- Smooth, invisible constraint (like God of War)

- No bumping, no falling off edges

**Technical Goal:**

- Extend vThirdPersonController without modifying base class

- Preserve Invector's input system and animations

- Support multi-section stairs with rotations

- Work with trigger-based path detection

...

Deliverable: Technical design document before any code.Claude proposed a clean architecture: extend vThirdPersonController, add a separate ControlPath component for waypoint management, use trigger colliders for path detection, and implement state transitions with a grace period to prevent exit flickering.

Phase 3: Phased Implementation

I asked the agent for a detailed implementation roadmap, reviewed it, and approved. Then, Press “Build”, the agent executed the plan systematically.

Full implementation plan: IMPLEMENTATION_PLAN.md

My role became testing and refinement. I compiled code, tested functionality, set up Unity scene waypoints, and tuned parameters. When issues emerged, I referenced the plan to provide targeted feedback. The agent understood the system architecture, so fixes solved root problems instead of patching symptoms.

The Result

Working code that I could actually test and refine. The player navigated waypoint paths, direction changes worked, and stairs functioned without constant collisions.

Perfect? No. There were still issues to polish and edge cases to handle better. But that’s development, no code is ideal on the first pass. The difference: this was functional and debuggable, not fundamentally broken.

It worked. Not flawlessly, but well enough to prove the concept and refine from there. That’s all you need from a prototype.

The Prompting Difference That Changed Everything

The real difference between approaches wasn’t just process, it was how I prompted the AI. Effective AI-assisted prototyping hinges on prompt quality and context.

Bad Prompt (Vibe Coding Approach)

The player can still rotate. Fix it.This prompt:

- Provides no context about why this matters

- Doesn’t explain the system architecture

- Offers no success criteria

- Forces AI to guess at the solution

- Results in tactical fixes without strategic thinking

Good Prompt (Tech Lead Pattern Approach)

# Context: Traversal UX Prototype for Stair Control

Goal: Demonstrate cognitive load reduction through smart constraints

Base: vThirdPersonController (Invector package)

# Current State:

+ Path detection working

+ Player enters path trigger correctly

- ISSUE: Player can still rotate left/right while on path

- This breaks the UX principle (should only move forward/back)

# Required Behavior:

When `isOnControlPath == true`:

- Disable left/right rotation input

- Allow only forward/back movement along path

- Preserve player agency over speed and timing

- Smooth transition in/out of constrained state

# Technical Constraints:

- Extend `vThirdPersonController` (don't modify base class)

- Preserve existing input system architecture

- Must work with existing camera system

- No breaking changes to ControlPath component

# Success Criteria:

1. Left/right input ignored while on path

2. Forward/back input moves along waypoints correctly

3. Rotation locked to path direction

4. Exit path = normal controls resume smoothly

5. No jitter, snapping, or sudden transitions

Please provide an implementation plan before writing code.This prompt:

- Gives complete system context

- Clearly defines the problem and why it exists

- Specifies exact requirements

- Lists technical constraints to respect

- Provides verifiable success criteria

- Requests planning before implementation

The difference in Claude’s responses was dramatic. The first prompt got a quick fix. The second got thoughtful analysis, potential solutions with trade-offs, and a proposal that considered the entire system.

The Tech Lead Pattern: A Reusable Framework

From this experience, I extracted a reusable prompting pattern I call the “Tech Lead Pattern”:

# Phase 1: Analysis & Understanding

Tasks:

- Review existing [component] architecture

- Identify extension points and dependencies

- Map current [feature] flow

- Document constraints and limitations

- List potential conflict points

Deliverable: Architecture analysis document

# Phase 2: Solution Design

Tasks:

- Propose class/component structure

- Define public API and interfaces

- Plan state transitions

- Anticipate edge cases

- Design for testability and maintainability

Deliverable: Technical design document

# Phase 3: Implementation Plan

Tasks:

- Break solution into 5-7 testable milestones

- Each milestone = independently verifiable feature

- Map dependencies between milestones

- Define review criteria for each gate

- Plan rollback strategy

Deliverable: Phased implementation roadmap

# Phase 4: Milestone Implementation

Process:

- Implement milestone 1

- Test against review criteria

- Get approval before milestone 2

- Repeat for each phase

- Document decisions and trade-offs

# Phase 5: Integration & Verification

Tasks:

- Integration testing

- Edge case validation

- Performance review

- Code cleanup and documentation

- Final review against original requirements

Please begin with Phase 1: Analyze the existing vThirdPersonController and provide your findings.Why This Works

1. Forces Architectural Thinking

The AI must answer:

- How does this fit the existing system?

- What dependencies need preservation?

- What could break as a side effect?

- What are the ripple effects?

This prevents tactical fixes that ignore system coherence.

2. Creates Review Checkpoints

Each milestone has clear success criteria:

- Milestone 1: Path detection → Review → Proceed

- Milestone 2: Input restriction → Review → Proceed

- Milestone 3: Smooth transitions → Review → Proceed

If something’s wrong, you catch it early when it’s easy to fix.

3. Provides Safe Rollback Points

Every milestone is stable and tested. If Milestone 4 goes sideways, you can revert to Milestone 3 without losing everything. No “lost in the weeds” moments.

4. Dramatically Improves AI Output Quality

More context = better code. The AI understands:

- Why you’re making this change (UX principle)

- What the existing system does (architecture)

- How to integrate without breaking things (constraints)

- When it’s working correctly (success criteria)

This reduces hallucination, prevents wrong assumptions, and results in code that actually works.

Real Example: Debugging with Context

The difference is stark when debugging:

Without Tech Lead Pattern

Me: "It's broken."

AI: "Let me add a null check."

[Doesn't fix the root cause, adds complexity]With Tech Lead Pattern

Me: "Player exits path too early. Here's the debug log showing

exit triggered immediately after entry. Analyze why this

happens given our path detection logic.

Log shows:

- Entry at position (10.08, 0.00, 1.15)

- Closest waypoint at (8.73, 1.93, 1.14) = 2.36m distance

- Exit threshold is 2.0m

- Exit triggered in next frame"

AI: "Analyzing the logs and code:

Root cause: Player's initial position is 2.36m from nearest

waypoint, which exceeds the 2.0m exit threshold. The entry

logic sets isOnControlPath=true, but the very next frame,

the distance check in OnTriggerStay triggers exit.

This is a race condition between entry state and exit validation.

Solutions (in order of preference):

1. Add grace period: Ignore exit conditions for 0.5-1.0 seconds

after entry. Simple, handles edge cases gracefully.

2. Increase exit threshold: Make it 3.0m to provide buffer.

Could allow too much drift from path.

3. Snap player to path on entry: Move player to nearest waypoint

immediately. Feels abrupt, breaks immersion.

Recommendation: Solution 1 (grace period). Maintains smooth feel,

prevents race condition, minimal code change.

Implementation: Add 'timeEnteredPath' float, check

'Time.time - timeEnteredPath > gracePeriod' before allowing exit."

[Clean, targeted fix that addresses root cause with reasoning]The second approach doesn’t just fix the bug, it explains why it happened, considers multiple solutions, and recommends the best one with clear reasoning.

Key Lessons for AI-Assisted Prototyping

1. AI is a Middle Developer, Not a Code Monkey

Treat it accordingly:

- Give it architectural context

- Ask for analysis before implementation

- Review its reasoning, don’t just accept code

- Challenge its assumptions

- Expect it to think, not just execute

2. Prompt Structure Matters More Than You Think

The formula:

- Context > commands

- Strategic > tactical

- Review-based > reactive

- Planning > immediate execution

Five minutes of writing a good prompt saves hours of debugging.

3. The Tech Lead Pattern Scales

This approach works for:

- Unfamiliar codebases (like Invector)

- Complex system integrations

- Production-quality requirements

- Team collaboration (prompts become documentation)

It reduces technical debt dramatically and produces maintainable code.

4. Vibe Coding Has Its Place and Its Limits

Use vibe coding for:

- Rapid exploration of ideas

- Learning new concepts

- Throwaway prototypes (not production AI-assisted prototyping)

- Personal experiments

Don’t use vibe coding for:

- Production systems

- Complex integrations

- Unfamiliar codebases

- Anything you need to maintain

5. Documentation Emerges Automatically

Good prompts create documentation as a byproduct:

- Architecture analysis → system documentation

- Design proposals → technical specs

- Review criteria → testing guidelines

- Milestone descriptions → implementation roadmap

Future you (and your teammates) will thank present you.

The Manual Comparison: Coming Soon

My original roadmap included building a manual control version of this prototype to establish a baseline. The goal was to capture concrete benchmarking data, specifically

- Time to completion (velocity)

- Total lines of code

- Bug density and debugging intervals

- Code maintainability and technical debt

- The friction of the learning curve

I skipped it for this article because it deserves its own deep dive. Coming soon: “AI vs. Manual: Building the Same Prototype Twice” where I’ll implement the exact same system from scratch and provide real data on the differences.

If you’re interested in this comparison, let me know in the comments, your interest will determine the priority.

The Future of AI-Assisted Prototyping

As AI models improve and development tools mature, AI-assisted prototyping will become standard practice. The key differentiator won’t be whether teams use AI, but how they structure their collaboration with it. Organizations that adopt systematic approaches to AI-assisted prototyping today will have a significant competitive advantage tomorrow

Takeaways: Your Design Checklist

Whether you’re building games, apps, or enterprise systems, here’s how to apply smart constraints effectively.

Traversal UX Checklist

Identify Friction Points

- Map collision points: Where do users bump into “walls” (literal or metaphorical)?

- List decision points: Which decisions add value vs. create friction?

- Record frustration signals: When do users backtrack, retry, or look confused?

- Note attention drift: When are users managing mechanics instead of enjoying experience?

- Measure cognitive load: How many micro-decisions happen in each interaction?

Design Smart Constraints

- Test constraint levels: Too loose = frustrating, too tight = restrictive

- Preserve agency over timing: User controls when and how fast, not necessarily where

- Make assistance invisible: Best constraints aren’t noticed consciously

- Provide clear feedback: User should know when constraints activate/deactivate

- Allow override when needed: Emergency situations need emergency controls

- Smooth transitions: Blend between free and constrained (0.2-0.5s minimum)

Implementation Guidelines

- Use structured paths: Waypoints, splines, or nav meshes for complex traversal

- Implement grace periods: Prevent flickering between constrained/free states

- Test with fresh eyes: Users unfamiliar with your design reveal friction best

- Measure objectively: Collision counts, completion time, error rates

- Iterate based on data: Not assumptions or personal preference

- Document the “why”: Future you needs to remember the reasoning

Validation Questions

Ask yourself:

- Does this freedom serve the core experience? If not, consider constraining it.

- Are users making the same mistakes repeatedly? That’s a sign of friction, not challenge.

- Could subtle guidance improve flow without removing meaningful choice? Test it.

- What would users focus on if we removed this friction? That’s your real UX goal.

- Does the constraint feel helpful or restrictive? Have users test without knowing it’s there.

- Can users articulate why they prefer one version? Often, they can’t, it just “feels better.”

The Design Philosophy

Characteristics of Good Constraints

- Feel natural and invisible during use

- Reduce cognitive load on mechanical tasks

- Free attention for meaningful decisions

- Enhance flow state and immersion

- Preserve player agency over timing and pacing

- Improve accessibility without feeling patronizing

Characteristics of Bad Constraints

- Feel restrictive or “on rails”

- Remove meaningful player choice

- Create frustration or confusion

- Break immersion with obvious hand-holding

- Solve problems users didn’t have

- Over-correct at the expense of feel

The Litmus Test

If users don’t notice your constraint system, you’ve succeeded. The best UX design is invisible.

If users praise your controls for feeling “smooth” or “natural” without knowing why, that’s smart constraints working perfectly.

If users complain about feeling restricted or losing control, you’ve over-constrained. Pull back.

AI-Assisted Prototyping Beyond Games

The same AI-assisted prototyping principles that worked for this Unity project apply across industries:

E-commerce:

- Smart defaults in checkout (saved addresses, payment methods)

- Constrained product filters (show 5-7 options, not 30)

- Guided size selection with fit recommendations

- One-click reorder for repeat purchases

Educational Technology:

- Progressive lesson unlocking (can’t skip prerequisites)

- Guided problem-solving with hints (constrained exploration)

- Auto-save and auto-submit (remove “did I save?” anxiety)

- Smart scheduling (system optimizes review timing)

Enterprise Software:

- Wizards for complex workflows (constrained step-by-step)

- Templates with smart defaults (80% pre-filled)

- Validation that prevents errors (vs. letting users fail first)

- Contextual help (appears when needed, not overwhelming upfront)

Mobile Apps:

- Gesture tutorials with constrained practice (can’t proceed until correct)

- Simplified navigation (3-5 main actions, not 15)

- Smart notifications (constrained timing and frequency)

- Onboarding flows that block until complete (prevents confusion later)

The pattern is universal: identify low-value friction, constrain it away, preserve high-value agency.

Conclusion: Big Lessons from Small Stairs

Let’s return to where we started: climbing stairs in two excellent games.

One tiny interaction. One moment that lasts maybe three seconds. And yet, it revealed something profound about UX design that applies far beyond games.

The lesson isn’t “constraints are good” or “freedom is bad.” That’s too simple.

The lesson is: the best design removes the decisions that don’t matter so users can focus on the ones that do.

God of War doesn’t remove player control, it removes player burden. You’re still in charge of when to move, how fast to move, whether to explore or progress. You’re just not in charge of “stay centered on these stairs” or “don’t bump into that railing.” Those are solved problems that don’t need your attention.

That’s smart constraint. That’s cognitive load theory in action. That’s invisible UX design.

And once you see this pattern, you can’t unsee it. It’s in every well-designed checkout flow, every intuitive mobile app, every smooth onboarding experience. The best interfaces guide you so gently you don’t realize you’re being guided.

The development lesson is equally important

AI-assisted prototyping is powerful, but prompting is a skill. Structure matters. Planning matters. The “tech lead pattern” isn’t just better than vibe coding, it’s the difference between maintainable systems and spaghetti code.

Give AI context, not just commands. Ask for analysis, not just implementation. Review systematically, not reactively. Your prompts should read like you’re briefing a middle developer, not issuing orders to a machine.

The lessons from this project extend beyond game development. AI-assisted prototyping, when done with structure and planning, accelerates innovation while maintaining code quality. The tech lead pattern transforms AI from a chaotic assistant into a reliable prototyping partner.

Final thought

Good design is often about what you prevent, not what you enable.

Great design makes that prevention invisible.

The best constraints feel like freedom.

Now go build something and prove it yourself.

Source Code: The complete Unity project, including both vibe coding and tech lead approaches, is available on GitHub: staircase-ux-study

Special thanks to the Invector team for the excellent third-person controller, Anthropic for Claude, Cursor AI for the AI agent integration, the VARTEQ team for their support, and Unity for a powerful game engine.

Author: Denis Panaskin